Basement Living And Grocery Business

A key lesson from the Airbnb era stands out: incentives, not just penalties, pull shadow units into the open.

Basement Living

Last week, City Hall unveiled new proposals aimed at bringing thousands of basement and cellar apartments—long operating in legal gray zones—into the light after years of tragic incidents and policy stalemate. The proposed rules focus on stricter safety standards, bans in flood zones, and financial incentives for small landlords, but underscore a deeper reality: the city continues to rely on an enormous informal rental market outside official oversight.

This shadow sector has long been—and remains—the only housing option for hundreds of thousands of unauthorized and unbanked New Yorkers who are routinely shut out of the formal market. In these arrangements, cash secures small rooms or basement units for $900–$1,200 a month: no lease, no paperwork, and, crucially, flexibility. Informal rentals also serve the city’s most mobile—newcomers, those between jobs, and individuals in transition—because this market offers the adaptability the formal sector cannot.

Much of this informal housing depends on personal connections. Newly arrived or precariously housed New Yorkers often find shelter through extended family, friends, or acquaintances, forming a web of mutual aid and opportunity. These networks foster rapid integration and resilience, but also make it exceptionally difficult to obtain reliable data on the size and conditions of informal arrangements.

Enforcement remains symbolic. Each year, the Department of Buildings receives over ten thousand complaints of illegal occupancy but issues only a few hundred vacate orders, recognizing that mass evictions would overwhelm shelters and destabilize neighborhoods. The city’s own 2019 basement pilot illustrates the hurdles: just eight units out of 8,000 approached remain in the program—retrofit costs averaged $275,000, far outstripping what these rents can sustain.

A key lesson from the Airbnb era stands out: incentives, not just penalties, pull shadow units into the open. When the platform provided guarantees, insurance, and reach, owners surfaced their apartments; when compliance became too costly or complex, hosts simply returned to the shadows.

For basement landlords, legalization means high upfront costs, inspections, and exposure—with little or no upside. If the city wants compliance, it needs to offer something meaningful in return. An Airbnb-style clearinghouse (Airbnb?) for safe, flexible rentals in mom-and-pop buildings could bring transparency, payment security, and mediation to at least some of this market, without sacrificing its adaptability. The alternative is shady arrangements via Facebook and Craig's list.

Still, many tenants and owners will remain wary, preferring discretion to documentation. For some, concerns about privacy, immigration, or simple mistrust will keep them in the shadows. Here, the role of trusted community leaders becomes essential. A robust “safe harbor” offering legal protection for units meeting core safety standards, realistic grants, and clear expectations is vital—not only for housing those at the margins, but for a citywide policy that matches the market New Yorkers actually use.

Mayoral Campaign Update

Democratic nominee for mayor Zohran Mamdani is on a two-week vacation to his native Uganda. But before he left, he met with Minority Leader Rep. Hakeem Jeffries, whose Brooklyn district Mamdani just won by 12 points. Jeffries had not endorsed him before the primary, and did not endorse him following their hour-long meeting. Does Mamdani need his blessing? Not everyone thinks so.

Mamdani also went to DC, but he has yet to charm Washington, where democrats are trying to figure out what to make of him and his win—only 4 of the 14 NYC representatives have endorsed him. Many establishment figures were unfamiliar with the assembly member from Queens before the election, The Times reports. Meanwhile, the Democratic Socialists of America are contemplating how they would wield power and influence policy.

In other news, Local 1199 SEIU, the city's powerful healthcare union with 200,000 members in NYC, is now endorsing Mamdani rather than Cuomo, as did Local 32BJ and the Hotel and Gaming Trades Council immediately after the primary, when the teachers' union also announced its endorsement. DC37 had endorsed him in the primary. It will be interesting to see how much leeway these late endorsements will give this very openly pro-union candidate when it comes to negotiations with the unions, should he be elected.

Errol Louis, meanwhile, notes that Adams is running on crime again, and wonders if that is a winning strategy for a mayor who "may have driven crime down so much that voters are ready to move on to rent, the price of food, and other issues."

Who Voted For Whom Where And Who Did Not

Since the primary results were released, analysts have been having fun dissecting the results, and the urban planner in me loves a good map. CUNY's Graduate Center has been mapping election data for decades, and offers the easiest way to visualize change across the city—a perfectly interactive place to see who voted how in the Democratic primary (you can plug in your address).

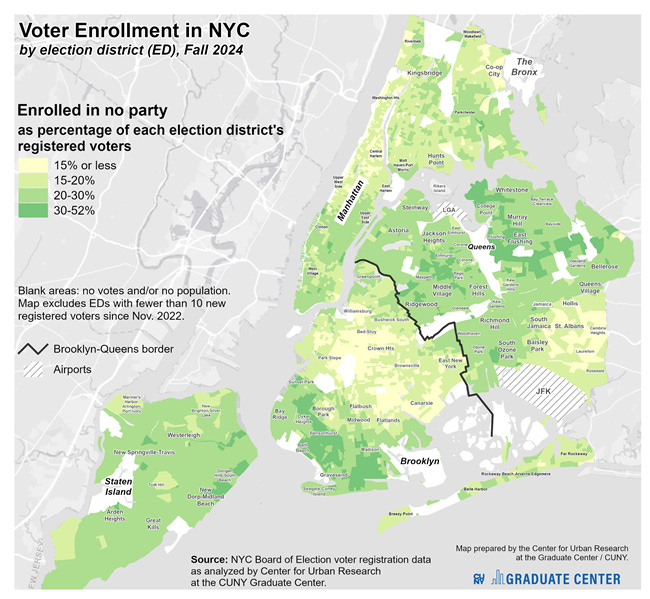

The dark green areas in the map above show which election districts have the highest proportion of unaffiliated voters. Interestingly, those were also, it turns out, some of the tightest districts in the Democratic primary — and may be the ones that help decide the general election.

Citywide, there are approximately 1 million unaffiliated voters — 21% of all registered voters as of 2024 — who will only be able to vote in the general election. Despite public support and a workable plan to change that, the Charter Revision Commission shelved electoral reform under pressure from progressive activists and officials, my colleague John Ketcham writes.

A couple of other interesting maps: City Limits examined how NYCHA residents voted and found that Mamdani was making inroads into formerly solidly Democratic establishment strongholds. And here you can see which NYC congressional districts Mamdani won, something that is undoubtedly keeping some democrats up at night.

Grocery Business

"Mr. Mamdani knows nothing about the grocery business, raising broader questions about the practicality of an assertive socialist agenda like his," MI's Nicole Gelinas writes in The New York Times.

"He claims that "a network of city-owned grocery stores" would offer cheaper food and dry goods because it would avoid paying rent or property taxes, "buy and sell at wholesale prices" and "centralize warehousing and distribution." These assertions collapse upon the slightest scrutiny."

Zohran Mamdani's proposal for city-owned grocery stores—one per borough to start—has struck a chord with voters angry over food prices and retail deserts, and has been the talk of the town this week.

In a New York Times guest essay, Fordham University professor Zephyr Teachout defends the idea as practical and overdue. She argues that large chains use exclusive supplier contracts and volume discounts to undercut independent grocers, inflating prices in low-income neighborhoods. Her proposal: ban price discrimination, enforce anti-gouging laws, invest in food hubs, and pilot city-run stores to restore fairness.

Gelinas offers a logistical reality check. Grocery retail is a low-margin, scale-driven business. New York lacks the warehouse infrastructure, supply-chain access, and promotional leverage to compete with national chains. Mamdani's claim that public stores could avoid rent and taxes is misleading: the city leases retail space like everyone else and would face higher labor costs. Gelinas also warns that city-run stores wouldn't just target big chains—they'd undercut the city's thousands of small bodegas and immigrant-run produce carts.

Meanwhile, Gothamist points out that New York already runs six city-owned public markets—such as Essex and Moore Street—offering discounted rent to local vendors. But these aren't full-scale grocery stores. Scaling them into a citywide supermarket network would be a different challenge entirely.

Howard Husock, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, argues in The New York Post that "capitalism—not socialist grocers—can fix NYC's food woes." He proposes delivery support for small retailers and regulatory reform—not city-run competitors—as the smarter path.

Kansas City has invested millions in a struggling city-owned supermarket, which, according to The Washington Post, struggles to keep its shelves stocked. In Chicago, Mayor Brandon Johnson has quietly backed away from a similar plan he once supported. Is New York so different?

Extra, Extra

A drone on patrol in NYC. Photo by Ed Reed/Mayoral Photography Office

Charter Revision: The 2025 New York City Charter Revision Commission Chair Richard Buery and its executive director, Alec Shierenbeck, joined Ben Max on Max Politics to discuss the proposals. Skip the first 22 minutes to get to the conversation.

Public Safety: A New York bill would ban ICE and other law enforcement officers from wearing masks during operations, as lawmakers respond to growing alarm over anonymous federal immigration arrests in city neighborhoods and a potential escalation in enforcement efforts across NYC [Politico, Gothamist, Hell Gate].

Real Estate: The city's Economic Development Corporation has indefinitely delayed a key vote on its $3.5 billion plan to redevelop the Brooklyn Marine Terminal, after task force leaders requested more time to address concerns about affordability, transit, and preserving industrial jobs. While maritime freight groups support the project, the delay underscores tensions over the plan's reduced housing, its reliance on private developers, and the city's attempt to bypass City Council review through a state-led approval process. [Crain's, The City]

Private Business: Developers keep swapping retail for members-only clubs— The Beginning in Brooklyn Heights and Moss at 520 Fifth Avenue, latest among them, tapping into a broader boom in luxury social spaces that cater to families, creatives, and wellness seekers alike. [Curbed, Crain's]

Meeting Place

Restaurant Week started on July 21 and will run through August 17. Here's your chance to explore all that NYC has to offer with 2-course lunches and 3-course dinners for $30, $45 or $60 at hundreds of restaurants across all five boroughs, but if you need some help, Infatuation looked for best deals, and crosscheck for spectacular rooftop views. Check details with restaurants about any restrictions.