Better Schools Require More Than Smaller Classes

In a rush to hire more teachers, NYC should focus on quality over quantity.

New York City wants to spend $602 million to hire 6,000 additional teachers.

The request, made by the schools’ chancellor at a recent budget hearing, is to comply with a 2022 state law that requires the city to reduce class sizes over several years. Under the law, elementary school classes must be capped at 20 students, middle schools at 23, and high schools at 25.

The reasoning behind the mandate is simple: smaller classes are expected to improve student learning.

But reducing class size by hiring thousands of new teachers is not the same thing as improving teaching.

Research has consistently found that a teacher’s effectiveness has a major impact on how much students learn. Students assigned to stronger teachers not only do better on tests but are also more likely to attend college and earn more as adults.

If the city focuses only on reducing class size without also strengthening teacher quality and retention, it risks meeting the mandate without meaningfully improving student outcomes.

The Challenges of Hiring at Scale

Hiring 6,000 new, high-quality teachers is also not simple.

In the 2022–23 school year, teacher preparation programs across New York State produced 12,930 graduates. New York City would need to hire nearly half that number to meet its numerical target.

Then there is the issue of retention.

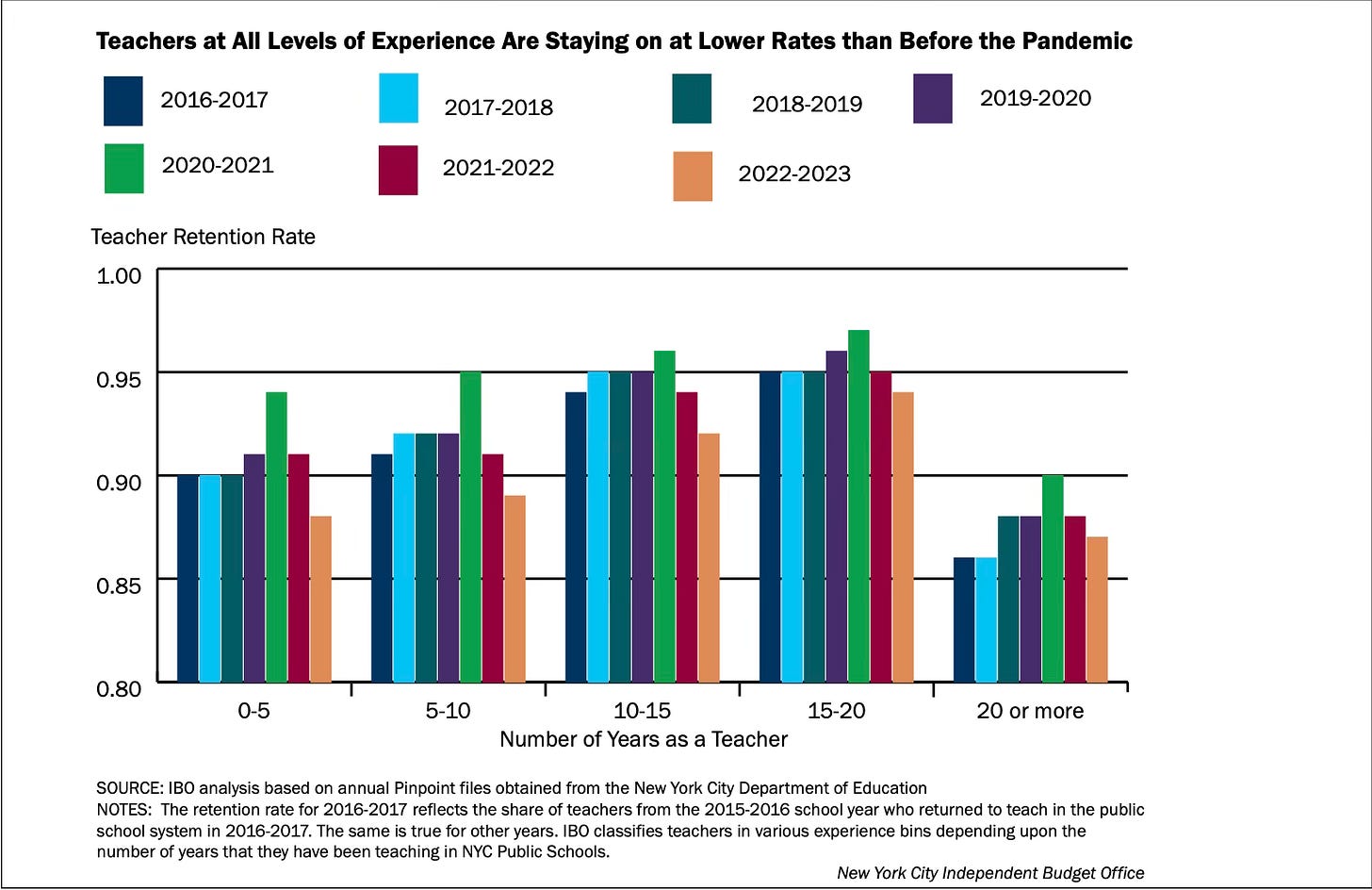

A 2023 report from the city’s Independent Budget Office found that teacher retention had fallen to 88%. Less-experienced teachers were leaving at even higher rates, and high turnover can hurt student learning. A large study of fourth- and fifth-grade classrooms in New York City found that when teacher turnover increased, student performance in reading and math declined.

If the city succeeds in hiring thousands of additional teachers but does not address turnover, it may simply be expanding a revolving door: more novice educators entering, more experienced educators exiting, and more students not learning.

Expertise Takes Time to Build

Teaching skills develop over time. Effective instruction requires subject knowledge, classroom management, familiarity with the curriculum, and practical experience. These skills are built through years of practice and professional support.

New teachers often enter classrooms with limited training in classroom management and the practice of teaching. To grow into strong educators, they need mentoring, coaching, and stability. If a system expands quickly without strengthening support for teachers, it can struggle to maintain consistent instructional quality.

The class-size law sets clear numerical targets, but compliance with staffing ratios is not the same as improved student achievement. Student learning depends on what happens inside classrooms: the quality of instruction, the consistency of expectations, and the stability of the school environment.

If success is measured only by whether class-size caps are met, policymakers will overlook whether students are actually learning more.

A Balanced Approach

Reducing class size may improve classroom conditions, but improving student outcomes also requires retaining effective teachers and supporting their professional growth.

In the short term, professional development could be more closely informed by teacher-reported needs, using existing survey data to identify priority areas for support.

The city already provides mentoring for first-year teachers. By focusing that time more intentionally and ensuring mentors have the resources to support novice teachers, the city could strengthen classroom practice without requiring additional funding. Supporting teachers so that they stay in the profession longer would also help build experience across schools.

As the city considers a $602 million investment during a looming budget crisis, it should be clear about what drives academic progress.

Hiring more teachers will reduce class size, but student outcomes will depend on whether NYC can recruit, develop, and keep highly effective teachers in classrooms, not just fill positions.

Smaller classes can improve conditions — more feedback, stronger relationships, fewer behaviour pinch points. But class size is an environmental lever. It is not, on its own, a quality lever.

The uncomfortable truth is that students experience teachers, not ratios.

If NYC hires 6,000 additional teachers without strengthening induction, mentoring, workload, and retention, the system risks diluting expertise just as it expands headcount. When turnover is already high, rapid expansion can unintentionally create more novice-heavy schools — and research is very clear that teacher experience and effectiveness compound over time.

There’s also a sequencing issue here.

Reducing class size may make it easier to teach well.

But it does not guarantee that teaching is strong.