The Radical Politics of Being "Stuck" in The City

Escape from New York is not so easy.

“If you don’t like it, leave” is a familiar New York response to complaints about cost or quality of life. It assumes that exit is easy and always available. But that’s no longer true, as the data below suggests.

Now, too many New Yorkers feel stuck in the city with few good options to improve their lot and the outsiders are finding it harder and harder to move to the city without having amassed a fortune already. The result of this breakdown in mobility is a rise in radical politics.

Exit, Voice, and Loyalty

New York’s current tensions reflect, in a very literal sense, the choices individuals make inside institutions described in the economist Albert Hirschman’s “Exit, Voice, and Loyalty,” an influential 1970 framework for thinking about organizational politics.

New York has always been a gateway city with high mobility. People come for the opportunity, stay long enough to benefit, and often leave later in their lives. These days, people still come, but at a high cost.

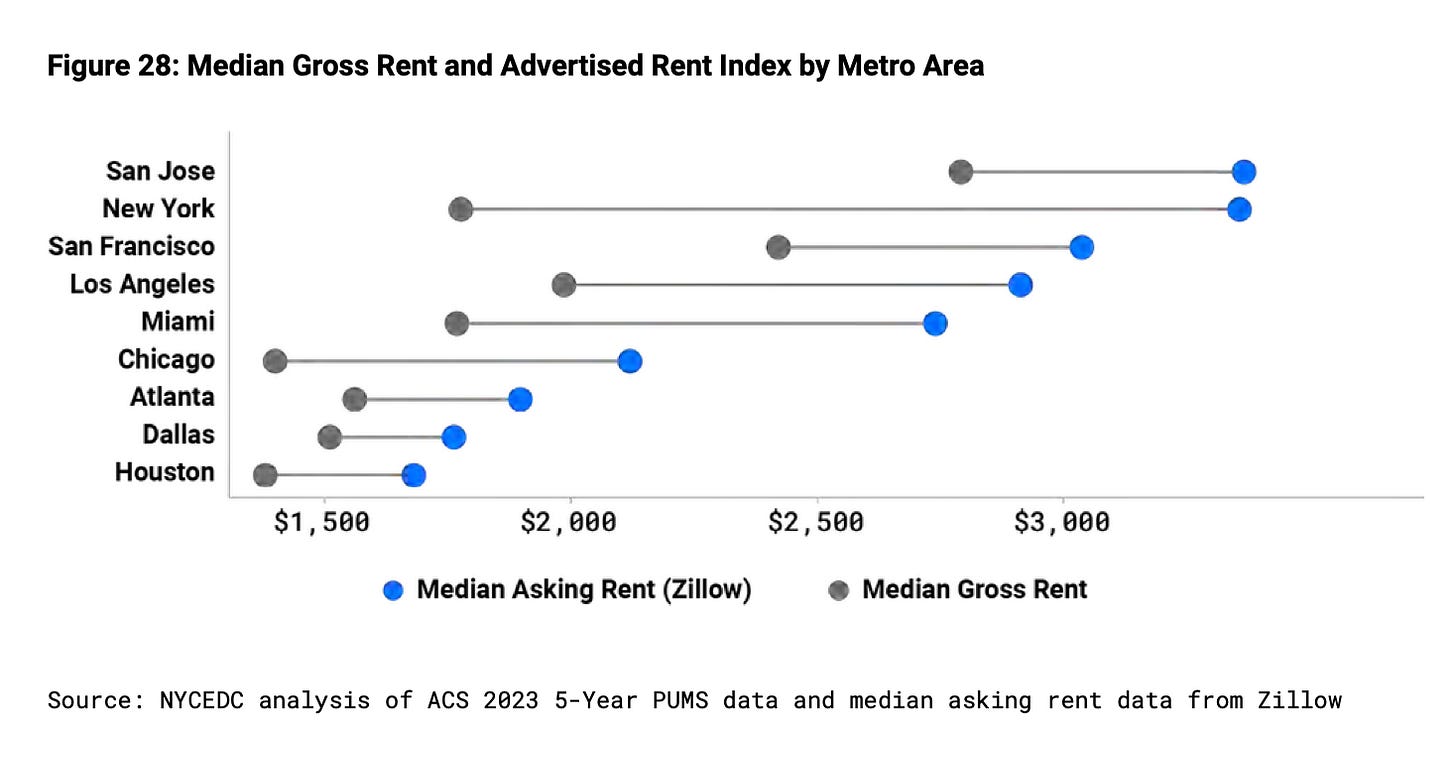

Housing costs have exploded for market-rate tenants, a trend particularly visible in the gap between the rents advertised to newcomers (the blue dot in the chart below) and the median rent in the city. It’s the widest gap in any major American city, and reflects a system of rent controls designed to protect incumbents from having to leave, with the side effect of repelling anyone who wants to come.

Childcare costs have also exploded, with particular consequences for the decision to stay. New York has always attracted people in their twenties and lost some share of households with children, especially young children. That life-cycle pattern long predates the pandemic and is not, by itself, evidence of crisis.

Timing

What is different now is when that exit occurs. The city’s cost structure means that expenses now arrive earlier in many parents’ professional lives than they can afford. They leave before they have a chance to make it, or they sink so much cost into the city that they find it psychologically intolerable to give up.

New York still offers opportunity: exposure to a high concentration of firms, industries, and networks that can change economic trajectories faster than elsewhere. But that opportunity only pays off if people can stay long enough to convert exposure into experience. Increasingly, they cannot. The city extracts labor, energy, and commitment early, then prices people out before they can collect.

Stuck

While some give up and leave earlier than they planned, there is a growing population for whom leaving is no longer a reliable solution. They have invested too much in staying, can’t quite make it, but exiting does not substantially improve their prospects.

Costs have risen nationally, and more importantly, regionally, as those leaving settle nearby, increasing demand, and pushing more people even further out. For many middle-income New Yorkers, leaving no longer guarantees lower costs, good jobs, and asset accumulation. Exit is still possible, but riskier, further away, and less advantageous.

Pressure Cooker

And when mobility stops functioning, political pressure builds. Residents remain not because conditions are acceptable, but because alternatives are limited. In Hirschman’s terms, “voice” intensifies when exit is blocked but loyalty has not yet collapsed, a pattern that maximizes political mobilization.

Zohran Mamdani resonated because he gave a political voice to the sense that the city’s opportunity bargain had become extractive. Unsurprisingly, support for the far-left candidate was strongest among young renters and early career professionals, recent arrivals, and middle-income families. Those are the groups most exposed to front-loaded costs and delayed rewards.

This all suggests that New York’s radicalizing politics are more due to the city’s economic structure than broader national ideological shifts. Mamdani’s voters are disproportionately located at the point where the city’s opportunity bargain fails, but where leaving remains too costly.

Unexpected Consequences

Progressive policies like rent regulation made cities more stable at the cost of mobility.

“Whatever its theoretical aspirations, in practice, progressivism has produced a potent strain of NIMBYism, a defense of communities in their current form against those who might wish to join them,” The Atlantic’s Yoni Appelbaum wrote recently. “Mobility is what made this country prosperous and pluralistic, diverse and dynamic. Now progressives are destroying the very force that produced the values they claim to cherish.”

These failed policies can be seen in Democrat-run cities across the country.

The solutions to New York’s rising “affordability” fight involve freeing the city’s housing market to improve mobility. But for Mamdani, doing so risks returning to more moderate politics.

The governor and state legislature can bail out the mayor from his promises. The two easy things that would unblock the worst aspects of his housing proposals would be to a) allow modest (greater of 3% or CPI?) increases in stabilized rents, and b) vacancy decontrol. As a sweetener to the mayor that would allow him to declare victory, how about giving him the 2% surtax on incomes above $1 MM that he's asked for? Ideally it would have a time limit (five years?) so that the city and state could figure out if the cost of such an additional tax is too high. Supposedly facing a $12 billion deficit, even a committed socialist should jump at a deal.

Given the great deal that most rent stabilized tenants already get, a modest annual bump would allow landlords to maintain property. Forcing them into foreclosure as a certain housing advisor to the mayor advocated prior to being appointed would lead to the city being their landlord, with no more resources available than what the landlord would have had. Does anyone in their right mind think that civil servants have the willingness or ability to keep them up to their present condition?

Vacancy decontrol is one of the easiest, politically speaking, means by which building owners can not only maintain but upgrade their properties. I've read somewhere (can someone confirm?) that there are 30,000 vacant rent stabilized units remaining vacant because they can not justify fixing them up within the 20% maximum increase allowed for vacant units.

For all its faults, California has a state law requiring vacancy decontrol for all municipal rent control ordinances. This has offset the worst of the effects of such laws. In that bulwark of free market economics, Berkeley, rents on recently rent controlled units that were only recently occupied have actually gone down, due to the construction of 1500 student dorm units, with another 1100 on the way (this in a trade area of perhaps 150K residents). It is possible to have a functioning housing market with rent control just as long as its proponents do not overreach.

Economists dislike price controls for a reason. Controls like rent controls. Yet the supply of housing is a political choice. Controlled by the need to win elections. When running a campaign takes a lot of money. Campaign finance money. Money that typically only comes (year after year, reliably) from the wealthy and special interests. Wealthy that LIKE the zoning laws and building codes. Laws and codes and practices that keep the cost of new housing high. Special interests that don't much mind the high cost of housing.

Yes, Mamdani was able to raise his money this time, but what about the other city council members?

Yes, there are matching funds for donations. Matches used mainly by the wealthy. Same donors, same message inflow into the elected members.

I write about campaign finance vouchers. it is a potential solution to NIMBY (over time). Take a look at Seattle. Caregiving has kept me away from Substack writing for about a year but check out what I got done up until then.