Mamdani, DSA, and co-governance

If Mamdani wins, we'll find out whether the socialist organization that built his career can wield real power in a complex, capitalist city.

Mamdani And The (DSA) Machine

Among the many stories about the rise of Zohran Mamdani, few have been as clear or telling as Michael Thomas Carter's piece for Dropsite, a decidedly socialist-friendly outlet. Mamdani's campaign was never just about one candidate: it was the result of a decade of organizing by the New York City chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America in working-class and immigrant neighborhoods, through tenant unions, labor drives, and strategic electoral challenges. The DSA's aim isn't simply to elect candidates but to build an infrastructure to help them govern.

The DSA's policy platform is online and worth a read: It defines socialism as "a vision of a humane social order based on popular control of resources and production, economic planning, equitable distribution, feminism, racial equality and non-oppressive relationships" and approaches economics with "a program of transformative regulation, nationalization, social ownership, and internationalism."

The DSA-NYC used to endorse progressive Democrats who shared some of their policy views. But now candidates must be openly socialist and willing to follow a coordinated policy platform. Mamdani has said he wouldn't have run without the group's endorsement, according to Carter. That means he enters office—if elected—with both a mandate and an obligation: to attempt structural change in how the city taxes, spends, and delivers services, with explicit support from the organization.

So, how do they plan to make that happen? As City & State reports, DSA is already organizing for the post-election phase. That means coordination between Mamdani’s team, DSA members, labor allies, and key Albany legislators. Regular strategy sessions with socialist lawmakers like State Senator Kristen González, aimed at passing new revenue bills and pushing back on austerity. Organizers will mobilize from the outside; electeds will steer from the inside.

Grace Mausser, co-chair of NYC-DSA, explains it as a co-governance model that links mass mobilization to executive power. The goal is to ensure policies like a city-run grocery network, free buses, and universal childcare don't stall once they collide with Albany or fiscal pushback. If Mamdani wins, we'll find out whether the socialist organization that built his career can wield real power in a complex, capitalist city.

Mayoral Campaign Update

Mamdani's first key meeting with business leaders at the Partnership for New York City on Tuesday made it clear he's not softening his agenda to make wealthy individuals and corporations pay more. While top Wall Street names like Jamie Dimon and Larry Fink skipped the session, those present noted his confident engagement, blending promise with challenge.

That posture is being watched closely by New York's Democratic leadership. Governor Kathy Hochul has so far publicly declined to endorse Mamdani, calling herself the city's "therapist-in-chief" and signaling discomfort with his "tax the rich"agenda. House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries has also held off on backing him.

Meanwhile, DSA-aligned organizers are preparing primary challenges in several New York City congressional districts, including NY-8 (Jeffries), NY-9 (Yvette Clarke), NY-10 (Dan Goldman), and NY-15 (Ritchie Torres), CNN reports. Jeffries's team has warned of a "forceful and unrelenting" response. For now, both leaders appear to be buying time — careful not to alienate either their progressive base or institutional donors, and notably leaving the door open to future alignment.

In New York, the broader friction isn't just policy — it's about party identity. Mamdani has shifted the Overton window: redistributive taxes, curbing executive power, and movement-aligned governance are now central to the political conversation. Progressives increasingly appear centrist; moderates are recalibrating in real time.

The former governor, having lost the primary, is back in the race and currently polling second. He wants other anti-Mamdani candidates to drop out by mid-September if they aren't polling in second place—a plan first proposed by Jim Walden and rejected by Eric Adams and Curtis Sliwa. A five-way general election favors Mamdani.

Adams, unlike Cuomo, had a very good fundraising cycle following the primary and raised $1.5 million, eclipsing Mamdani, though both men reported almost half their donations came from outside the city (NYT). And lastly, following a feisty hearing where it was framed as an attempt to overturn the historic primary election by some, the question about open primaries will not be on the ballots in the fall. (THE CITY)

Risks Of Decentralizing Power

Mamdani has called for the mayoral control of public schools to be replaced with a co-governance model that empowers educators, parents, and communities. He wants to "give the public a firmer hand in guiding housing development across New York." And his critique of executive authority aligns with a broader effort to decentralize city government.

But decentralization, in practice, can mean fewer decisions get made.

In New York, land use is already shaped by community boards, borough presidents, and councilmembers. As MI's Eric Kober has noted, this structure creates multiple veto points that routinely stall housing, even in high-opportunity neighborhoods. Mamdani proposes developing a Comprehensive Plan for the city to facilitate housing development, but doing that through democratic consensus building will take time and won't be easy.

The school system could be heading in a similar direction. Recent changes to the Panel for Educational Policy (PEP) expanded its membership and limited the mayor’s ability to replace appointees. While mayoral control remains on paper, its effectiveness is weaker already, and analysts warn that what’s emerging is slower and more politicized decision-making. And before mayoral control in 2002, New York’s school system was known for patronage and paralysis.Mamdani's plans are currently too vague to be reassuring.

Mamdani wants to share power. But without structural clarity, shared power often means shared paralysis. He argues that redistributing power would bring decisions closer to communities. And in theory, that could mean more democratic input. In practice in New York City, however, that often means handing power to those who are best organized and benefit from it most directly— public sector unions and city-funded nonprofits, among others.

Without strong, clear alternatives in place, decentralization can also create more veto points, slower execution, and less public clarity about who’s responsible when things break down. When you weaken the mayor’s office, decisions still get made, just further from public view, and often by people with less public accountability.

Gotham’s Looming Fiscal Crisis

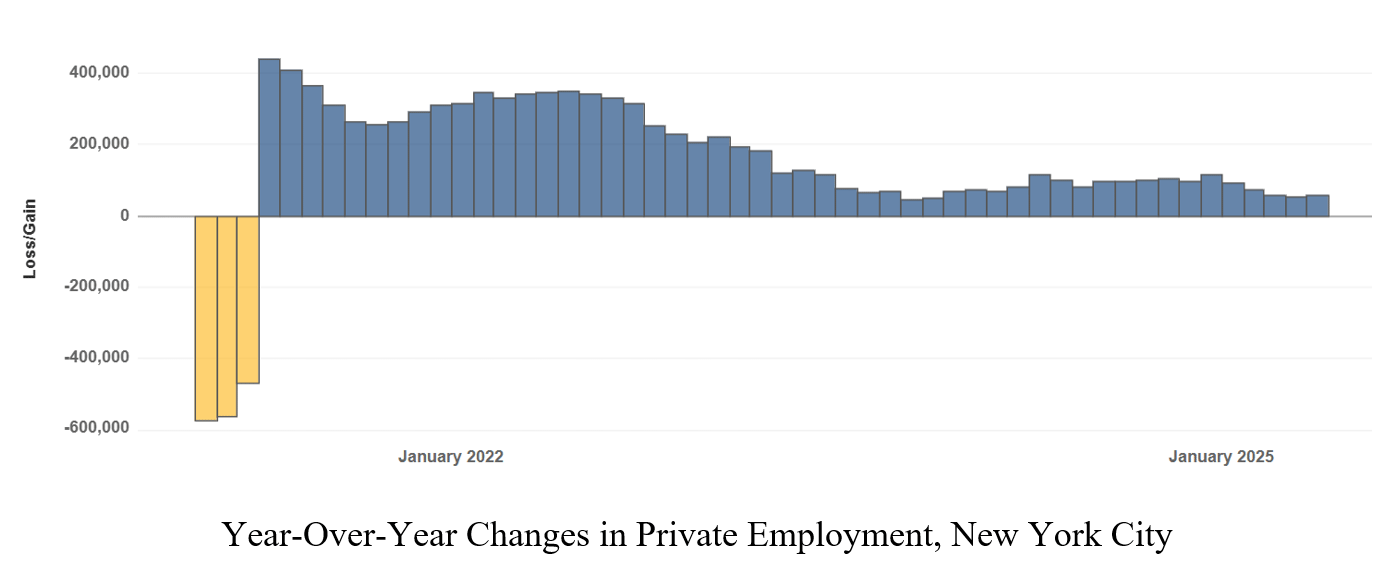

Notwithstanding the candidates’ plans, the next mayor may be forced to make budget cuts, Eric Kober writes in City Journal. New York City’s labor market is weakening, with job growth driven largely by Medicaid-funded home care. Core sectors like construction, retail, and finance remain flat or shrinking, casting doubt on the revenue assumptions behind expansive progressive agendas.

Wet Work

After Monday’s deluge dumped over 2 inches of rain in just an hour, one of NYC’s quietest flood defenses kicked in: the curbside rain garden. The city has now installed more than 11,500 bioswales—planted street pits designed to soak up stormwater before it floods intersections or overwhelms sewers. Each holds about 2,500 gallons per storm, and 2,300 more were added last year, mostly in flood-prone areas like East Flatbush and Queens. The goal: capture 668 million gallons annually by the end of 2025.

At $15,000–$20,000 each, bioswales are the city’s most cost-effective tool for reducing sewer overflows. They aren’t built to handle full-scale cloudbursts like Monday’s on their own—but by slowing runoff and absorbing water at the block level, they help blunt the surge and buy time for the rest of the drainage system.

So why aren’t they everywhere? In Manhattan, a dense web of underground utilities—steam lines, subways, water mains—makes many streets too congested to safely dig. That’s why the city has focused bioswale construction in the outer boroughs, while relying on green roofs, blue roofs, and underground tanks in denser neighborhoods.

The program isn’t flawless—maintenance remains a challenge, and the City Council is weighing legislation to require better community notice—but bioswales are helping NYC adapt, block by block, to storms that are coming faster and hitting harder.

Extra, Extra

Education: Former NYC Schools Chancellor David Banks discussed mayoral control and other topics with Marcia Kramer (CBS). New York State is plans to eliminate Regents exams as a mandatory graduation requirement—a move aimed at reducing standardized-testing pressure (Chalkbeat).

Childcare: The City announced a $10 million universal childcare pilot for children under two, starting in 2026, and $70 million for special needs preschoolers. (NYPost)

Housing: Comptroller Brad Lander’s report found that NYC’s office-to-residential conversions could create up to 17,000 housing units, mostly in Manhattan, but warned that proposed tax incentives may unnecessarily cost the city billions, since many projects are likely to move forward without them.

Real estate: Six new buildings on a block in Queens will have 591 units among them, with none exceeding 99 units. “The 99-unit cutoff is likely an example of how some real estate industry leaders say developers are getting around one of the new rules for the affordable housing tax break 485-x, which includes a $40-per-hour minimum wage requirement on all projects with 100 or more units.” (Crain’s)

Labor: The City Council approved two bills that expand labor protections to grocery delivery workers, ensuring they receive the same minimum wage of $21.44 and the same rights as restaurant app couriers. (Gothamist)

Small Business: New York’s small business health insurance market teeters on the edge of collapse (Fiscal Policy Institute)

Meeting Place

Oceana (120 W 49th St) is a go-to for an elegant Midtown lunch—refined without being showy, with a $37.50 three-course menu that hits the sweet spot between impressive and efficient. The room is calm, the tables are well spaced, and the noise level stays low enough for an actual conversation.