"Rental Ripoffs" and Economic Realities

The distressed buildings need income and currently have no way to get it.

Moving fast, Mayor Mamdani announced Sunday both the appointment of a new housing commissioner, Dina Levy, and that the city will hold “Rental Ripoff” hearings in all five boroughs to expose “poor conditions” and “unconscionable business practices” the city will then “act upon.”

There’s an interesting juxtaposition between the city’s beneficence to affordable housing developers and its ruthless crushing of rental landlords, for Levy takes over a vast affordable housing development subsidy operation which by design has essentially subsumed the city’s private housing development industry.

Affordable Housing Development Subsidies

Most of the new housing HPD subsidizes is built by private developers. They don’t do it out of charity, nor should they; the developer’s fee is built into the term sheet.

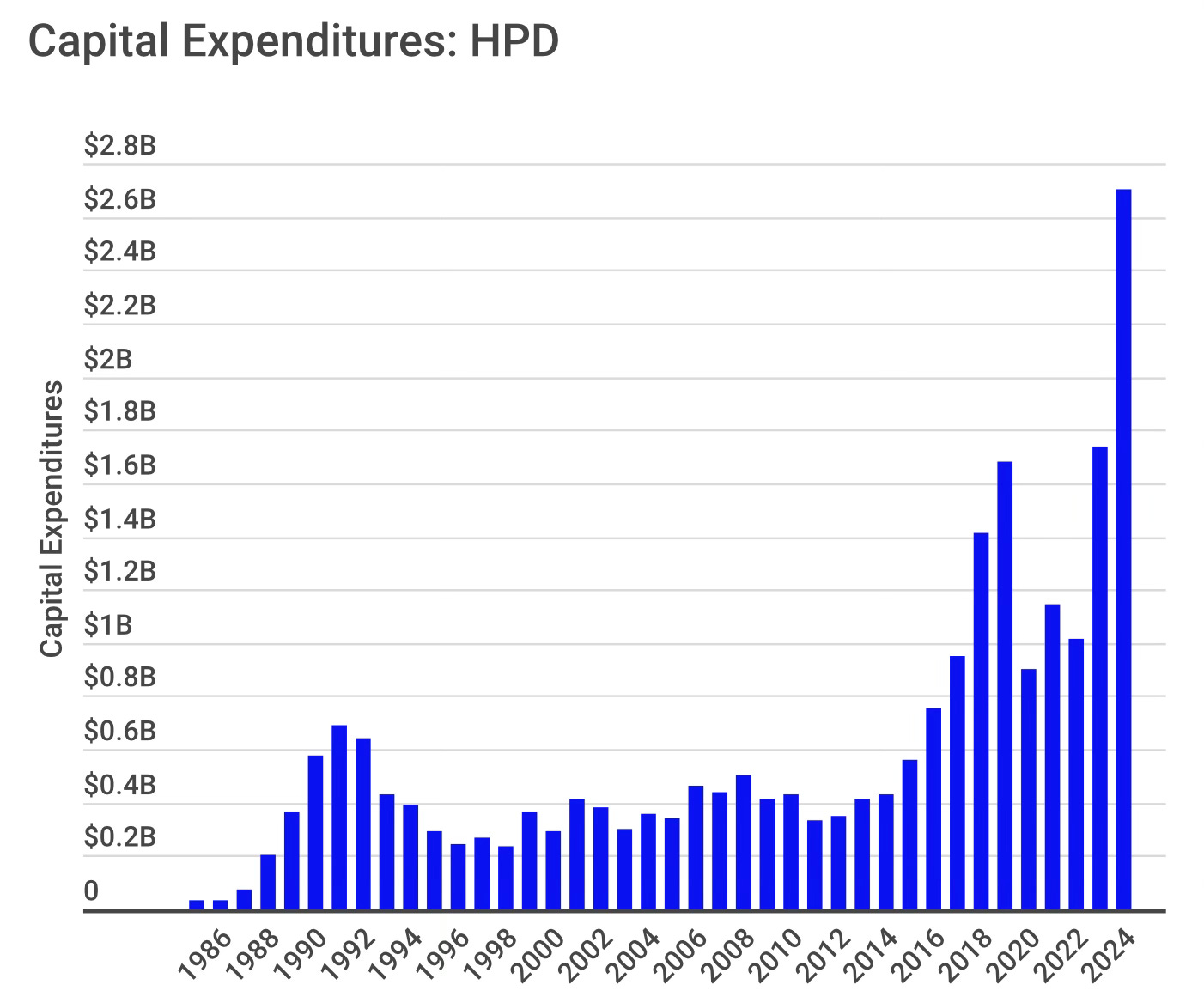

Below is a graph, produced by the city’s Independent Budget Office, showing the Department of Housing Development’s capital (new construction and rehabilitation) expenditures by fiscal year (FY; city fiscal years begin on July 1 of the prior calendar year).

Since Bill de Blasio took office as mayor in the middle of FY 2014, spending has shot up, well outpacing inflation. The funding increases paid for a big jump in the number of affordable housing units the city builds and rehabilitates each year. The city also has made a large capital commitment to repairing its deteriorating public housing.

And that’s not all. The city also underwrites new housing construction by foregoing property taxes. In FY 2025, the exemption for private for-profit housing, known as Section 421-a, cost the city nearly $2 billion, and the exemption for non-profit, 100 percent affordable housing, known as 420-c, $479 million.

There is more coming, through new tax exemption programs the state legislature enacted in 2024: Section 485-x, for new housing construction, and Section 467-m, for conversions of commercial buildings to housing.

Contrast the affordable housing developers, who the city lavishly subsidizes, with the owners of rent-stabilized housing, who face the full wrath of Mamdani’s about-to-be-mobilized administration.

Rent-Stabilized Housing Financial Crisis

There are no doubt bad actors among rent-stabilized landlords, but let’s put the blame where it belongs.

The Housing Stability and Tenant Protection Act of 2019, the draconian 2019 rent law that foreclosed most of the ways that rent-stabilized rents could rise close to market levels, effectively incentivizes bad behavior. Like all price controls, it leads to shortages – the rental vacancy rate has plummeted – and black-market activity, like demands for under-the-table payments that are condemned in Mamdani’s press release.

Mamdani has inherited, thanks to HSTPA, a financial crisis among the rent-stabilized housing stock. Recent research by the NYU Furman Center indicates that the distress is concentrated in two categories of rent-stabilized housing: “Legacy 90%+ Rent-Stabilized Properties” and “Government-Subsidized, Income-Restricted Rent-Stabilized Properties.” The former comprise 456,000 rent-stabilized units; the latter, 183,000. (There are about one million rent-stabilized units overall).

So, the “Rental Ripoff” hearings will likely lead to lots of revelations of bad building conditions and bad landlord actions. But then, the problem arises: what will the city do about it?

There’s No Money

The distressed buildings need income and currently have no way to get it. The fundamental problem is HSTPA, which Mamdani seems to regard as a crowning “pro-tenant” achievement; he appointed Cea Weaver, who was a key advocate of the bill’s passage in Albany, as director of a revitalized Mayor’s Office to Protect Tenants.

There’s no indication that this is all a political smokescreen for a pragmatic effort to pass amendments to HSTPA to mitigate its worst effects. Albany doesn’t work that way, and the city’s and state’s leading Democratic politicians have staked out positions precluding it.

The city could throw the book at bad landlords and impose punitive fines; but the buildings do not generate the income to pay fines. The city could go to court and seek the appointment of an administrator to collect rents and make repairs. Where rents are insufficient to pay for repairs, the city could pay for repairs itself and put a lien on the property to recover its outlays upon sale. However, the distressed buildings would not sell at sufficient value to recover such outlays.

The city can’t simply make the repairs gratis, since that would increase property values and enrich bad-actor landlords at no cost to themselves. That leads to another course of action – foreclosing on the liens and taking distressed buildings into city ownership. Either the city would operate the buildings itself, bearing the operating and repair losses through its budget, or transfer the buildings to non-profits – but that would also require ongoing subsidies borne by the city.

City’s Poor Record

The city has actually gone down this particular rabbit hole before.

In the late 1970’s, Mayor Edward I. Koch’s administration responded to criticism of the round-robin nature of auctions of property-tax delinquent properties. Buildings would be auctioned, sold and then auctioned again when the new owner failed to pay property taxes. The city’s housing commissioner, Nathan Leventhal, later deputy mayor, thought the city could use surplus Federal Community Development Block Grant funds to manage distressed buildings directly.

The Department of Housing Preservation and Development set up, in effect, an alternate public housing authority called the Office of Property Management (OPM). A Division of Alternative Management Programs was also set up, to transfer buildings to non-profits and tenant coops. A 1982 New York Times article reported the city was then managing 35,000 occupied units.

City management rapidly became a fiscal drain that outpaced the availability of Federal funds. Inexperienced city property managers were unable to collect rents owed or repair buildings. OPM staggered into the administration of Mayor Rudoph Giuliani, who ended city management by privatizing the buildings to “neighborhood entrepreneurs,” considered responsible landlords. There wasn’t much political opposition by then.

Risks of Repeating History

I fear that we are heading for a replay of this history, in a far richer city where the housing is distressed not because of underlying economic conditions but simply because the state legislature has willed it.

But look at the data on existing city spending on housing, even before it has taken on this responsibility. And look at the sheer size of the distressed housing stock we could be talking about. The resources available simply aren’t going to be enough.

To get an idea of what happens when politicians’ promises collide with fiscal realities, look at another giant stock of distressed housing that Mamdani didn’t mention at his Sunday press conference: public housing, with its estimated $80 billion in capital needs. It will be hard for Mamdani’s appointees to keep NYCHA tenants out of the “Rental Ripoff” hearings.

In the end, someone has to pay to maintain the city’s rental housing stock. Showy hearings and berating landlords won’t pay the bills.

Do the HPD chart figures include the exploding growth of the CityFHEPS program? See: https://cbcny.org/research/cityfheps-hits-1-billion

The Koch-era parallel is instructive but probably understates the scale issue here. When OPM collapsed in the 80s, the city was managing 35k units. The Furman data suggest 640k rent-stabilized units across two categories are now financially distressed under HSTPA's constraints. I ran numbers on a few portfolios in the outer boroughs last year, and the disconnect between regulated rents and actual operating costs has gotten absurd. Buildings can't even cover property taxes + insurance anymore, let alone capital improvements. The perverse part is the "Rental Ripoff" hearings will document real problems but the only solution that scales requiring Albany to tweak HSTPA's rent adjustment caps is politically radioactive. So we're probably heading for some hybrid mess where the city takes on partial management responsiblity without full ownership, bleeding budget capacity that could've gone to actually building new supply.