Sushi at Your Door Isn’t “Essential”: Rethinking New York’s Delivery Debate

What’s “essential” work in New York now?

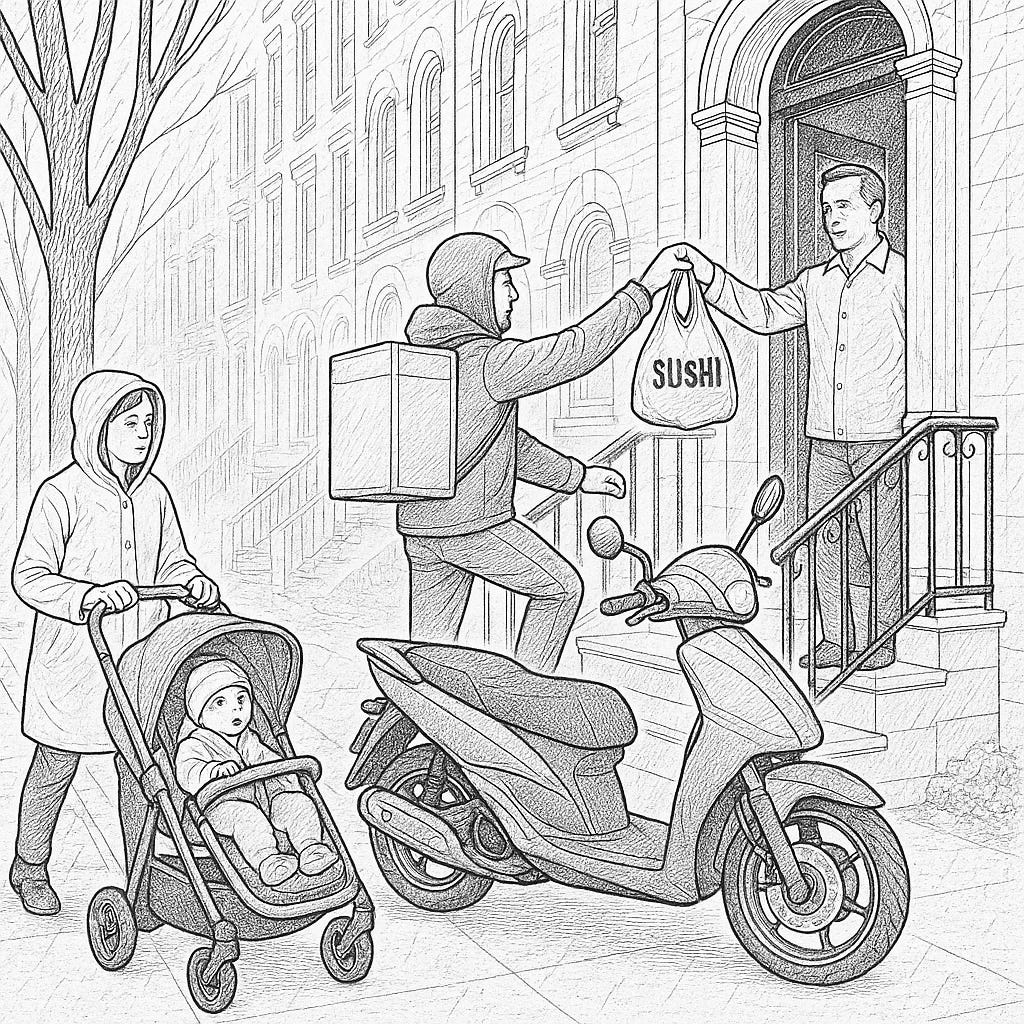

A sushi delivery on a rainy night may feel like a modern miracle, but is it “essential”? What about your right to a fake Gucci bag?

That seems like a silly question, but New York politicians are on the verge of expanding the category of “essential worker” as the city heads to the polls in a mayoral race that reflects very different views of how the city should function.

The recent conversation on this subject began after federal immigration raids on vendors selling often-counterfeit merchandise to tourists on Canal Street. (According to the Department of Homeland Security, nine of them were in the country illegally.)

In response, the Street Vendor Project and Los Deliveristas Unidos joined forces to demand greater protection from City Hall. Their leaders call their members “essential workers.”

But as New Yorkers and policymakers debate the rights and regulation of deliveristas — the city’s vast, mostly immigrant food-courier workforce — and other marginal workers like street vendors, it’s worth drawing a sharper distinction between what sustains a city and what simply caters to convenience.

“We’re trying to hold onto the moment coming out of the pandemic when people finally realized that deliveristas are essential workers,” NYC councilmember Justin Brannan said of his bill that would prohibit app-based delivery services from deactivating workers without cause.

Brannan, a supporter of Democratic nominee Zohran Mamdani, speaks for his party’s ascendant, pro-labor left. He also reflects an effort to protect workers without legal status from the federal government — in the case of the market on Canal Street, by effectively legalizing selling counterfeits.

But that expansion of the idea of what’s essential overlooks obvious realities of urban life. Delivery workers may be a growing political force, but food delivery is the opposite of an essential service. It’s a choice made possible by a sprawling digital and labor infrastructure that, while economically significant and highly visible, is ultimately optional for the vast majority of New Yorkers — and has real downsides.

The Role of Delivery in Modern NYC

App-based food delivery has embedded itself in the routines of millions, driving over $120 million in consumer spending just in the first quarter of 2025 in NYC alone. With fierce competition, app promos, and neighborhoods saturated with options, ordering in for lunch or dinner has become a middle-class norm, not an emergency stopgap or social equalizer. Approximately one-third of New Yorkers order delivery weekly, a trend fueled further by gig platforms courting both eaters and eateries with frictionless digital convenience.

But “essential” is a loaded, policy-laden term. New York law defines essentials as services genuinely necessary to physical survival or the functioning of society—such as medical care, pharmacies, groceries, and transit. Sushi, tacos, or pizza, ordered from an app and carried on an e-bike, are not required to sustain life. For all but the frail, sick, or housebound, there are alternatives: cooking, grocery shopping, or simply calling a neighborhood restaurant for takeout.

So Why Call Deliveristas “Essential”

There are real reasons for advocacy around delivery work. The food delivery sector creates tens of thousands of jobs—overwhelmingly filled by immigrants, many of whom have limited legal protections. Delivery keeps some restaurants afloat in an era of rising rents and shrinking profit margins. App-based work has become the economic backbone for families and communities that rely on flexible hours and low barriers to entry.

But the claim that this arrangement is essential—rather than economically important, convenient, and at this point, heavily ingrained—confuses labor politics with urban survival. Rules debated in City Hall about minimum wage, workplace safety, and platform regulation are about labor dignity and market fairness, not about whether the city can function without poke bowls arriving by scooter.

City leaders idealize deliveristas for political and ideological reasons. Turning gig workers into urban icons signals compassion, inclusion, and virtue while avoiding more contentious policy debates. Lawmakers and advocacy groups claim they are protecting the city’s backbone, but imposing such rules and regulations is likely to lead to fewer jobs for New Yorkers (California’s AB5 provides a good case study).

Neighborhoods and Quality of Life Impact

The reflexive defense of this new service industry has other costs. The surge in delivery has altered the streetscape with fleets of e-bikes and scooters. It’s also created new frictions around curb use, street safety, survival of brick and mortar restaurants and worries over “ghost kitchens.”

“I don’t know if people realize or recognize the consequences of this,” Collin Wallace, formerly of Grubhub, told The Atlantic of delivery’s wide adoption. “I don’t know if they actually understand what they’re paying when they place a delivery order. Whether it’s infrastructure, whether it’s the restaurants or the character of their local neighborhood or just the sheer dollars. I don’t think they necessarily know.”

Apps facilitate this convenience, and many independent restaurateurs—who once built neighborhood character— are struggling. Instead of drawing residents together over a meal, delivery channels them into lonely, atomized, privatized consumption far from civic interaction: 30% of meals that used to be eaten in these restaurants are now delivered, and it keeps growing.

Convenience Isn’t a Civic Necessity

I don’t mean to diminish how hard the deliveristas are working, often on cold, wet days like this one, to do their jobs. They’re among the strivers who give New York its energy.

But at this moment of change, the debate over what’s “essential” should force us to be honest with ourselves and our city. Making delivery safer and fairer is a legitimate goal—but that doesn’t mean it should push aside other values. The things New York truly can’t live without—emergency care, clean water, the subway, housing—deserve the “essential” label. Sushi arriving within 30 minutes does not.

If policymakers and advocates ceded the language of “essential” to its original meaning, we’d have a clearer, more honest debate about how to best support workers, restaurants, and neighborhoods. We could invest in real essentials—and appreciate delivery for what it is: a remarkable, valuable, but ultimately nonessential urban luxury.

Image generated by AI

Everything is essential to someone. What is and isn't essential is an inherently personal and subjective matter.

And the spending on the delivered meals is also considered essential by supposedly strapped households.