Preservation Has Costs. Housing Is One of Them.

Should City Hall reconsider landmarking Flatbush?

City Hall is about to make a land-use decision that will affect Brooklyn’s housing supply for generations.

Two historic district designations in Victorian Flatbush will soon be headed for review and approval. These approvals are usually treated as formalities, and the council tends to defer to the local councilmember.

But the new City Council should reconsider that practice, as large-scale landmarking is one of the most restrictive—and permanent—forms of de facto zoning New York City has.

Approving these districts will preserve more of Victorian Flatbush, but will also permanently limit housing growth in Ditmas Park, a neighborhood with direct and easy access to Midtown, at a time when the city is in a deep housing shortage.

And Mayor Mamdani, running on a platform of expanding housing, does not have to automatically sign off on these new restrictions, and he shouldn’t.

Preservation Is a Housing Policy

New York’s Landmarks Law is premised on the idea that preserving architecturally and historically significant buildings and neighborhoods can protect heritage, stabilize property values, strengthen the economy, and improve quality of life.

To qualify as a historic district, an area must represent a recognizable architectural period, have a coherent streetscape, and convey a distinct sense of place. The law says nothing about the size of such areas.

The problem is that, through landmarking districts, we do more than freeze buildings in time; we effectively permanently limit growth in an area without considering the future development potential of the wider neighborhood and the city.

The Landmarks Preservation Commission evaluates architectural and historic merit. It is not tasked with balancing other policy concerns — housing supply, affordability, climate goals, or transit-oriented development. Those considerations are left to the city’s planning agency, which reviews landmark designations after the fact for compliance with existing rules and zoning, and, since there are usually no changes to the current conditions, generally approves the proposals.

In effect, a body focused on aesthetics is making irreversible land-use decisions in some of the city’s most valuable locations.

New York’s neighborhood-scale historic districts cover hundreds and even thousands of buildings at once. The combined Park Slope Historic District includes more than 2,000 buildings, making it the largest in the city by that measure. As the neighborhood gentrified, brownstones were restored, and surrounding development pressure increased, the original Park Slope Historic District expanded—twice.

The result there and elsewhere is that large, prime areas near subway lines, parks, and commercial corridors are locked into low-density use indefinitely, driving up rents as demand soars. At a moment when the city is struggling to meet even modest housing targets, such choices have public costs.

A Suburban Enclave on the Q Line

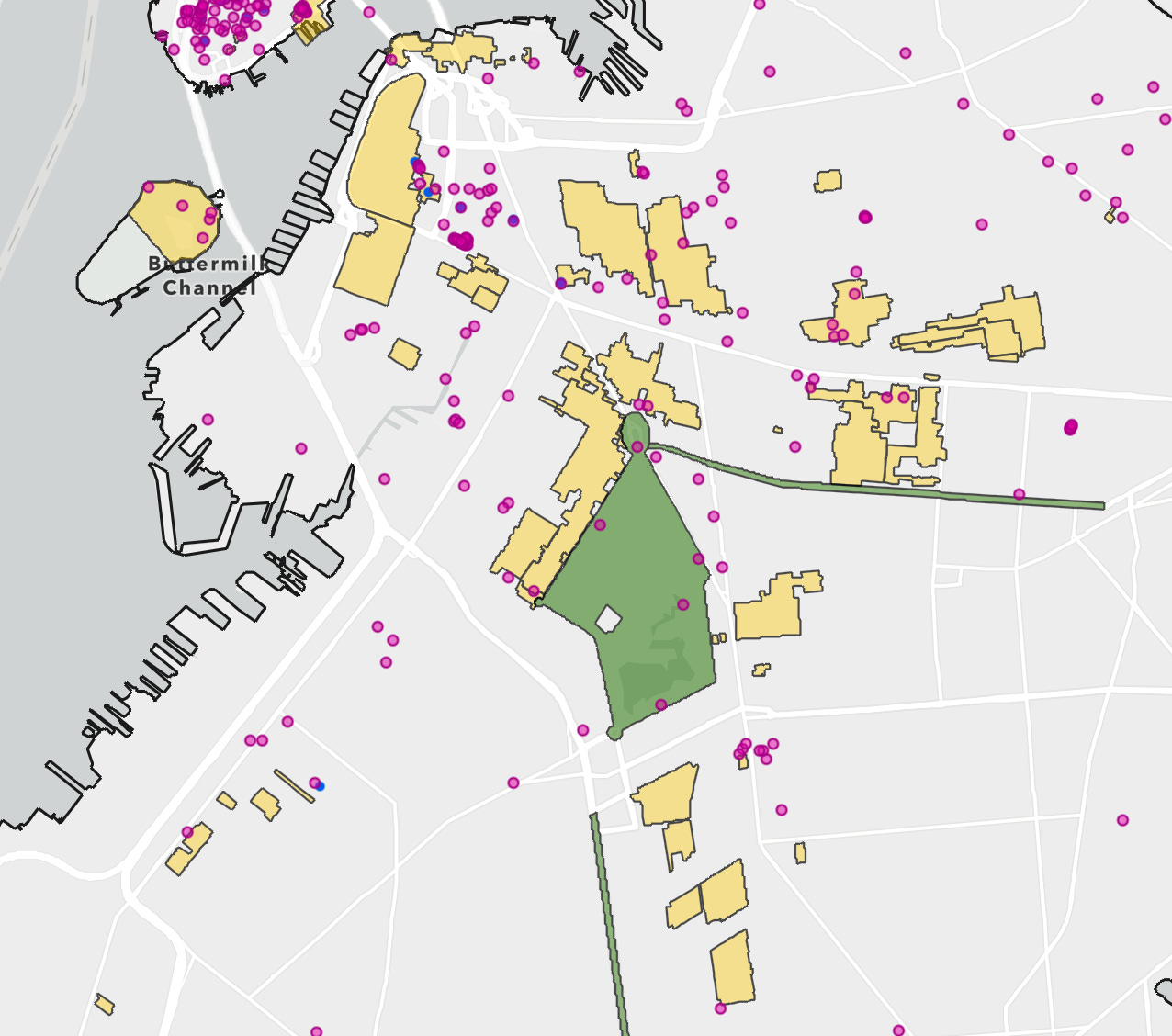

The proposed Beverley Square West and West Midwood districts sit along the Q line in Victorian Flatbush. Together with already designated Prospect Park South, Ditmas Park, and Fiske Terrace-Midwood Park, they form a near continuous band of low-density, detached housing within roughly a 45-minute commute of Times Square. Combined, these districts cover nearly 9 percent of Community Board 14 land area.

The Beverley Square West designation is particularly illustrative of another issue that goes unaddressed – the broader impact on the community. The district directly abuts the Cortelyou Road commercial corridor. Cortelyou Road is a short but active strip, yet portions of its edge between Stratford and Marlborough Roads are lined with detached houses that contribute little to street life.

One of the houses was excluded from the historic district because it had been altered too much. Another was kept, subjecting the neighborhood to over 100 feet of plastic fencing in the heart of the strip for the foreseeable future with no discussion of the impact that I could find.

Several six-story mixed-use buildings already exist on Cortelyou Road and fit comfortably into the neighborhood. Across the street, three- and four-story mixed-use buildings line the strip. Under landmarking, similar development is no longer possible at the corner of Cortelyou and Argyle Roads.

The designation treats Cortelyou Road as a boundary rather than a public asset. That is backwards.

“Character” Was Already Regulated

Supporters of landmarking often argue that it is necessary to protect neighborhood character. But in Victorian Flatbush, that work was already done.

In 2009, the city contextually rezoned the area, and much of Victorian Flatbush was restricted to detached one- and two-family homes. The explicit purpose was to preserve neighborhood character. City of Yes for Housing Opportunity did not change that.

The key difference is that zoning can change. Landmarking doesn’t.

While historic designations are technically reversible, they are intended to be—and in practice are—permanent. That means the city is locking in land-use decisions based on current preferences for what to preserve and how much of it.

Planning Review in Name Only?

By law, landmark designation is effective upon the Landmarks Preservation Commission’s vote. After the LPC designates a historic district, the City Planning Department reviews how it relates to zoning, infrastructure, and plans for growth. In the Beverley Square West and Ditmas Park West cases, the department reported to the City Planning Commission it was “not aware” of any relevant plans that would conflict with the designation.

There was no serious public accounting of how the proposal would effectively freeze development in perpetuity, nor a broader neighborhood-wide planning review to consider how permanently displaced housing capacity should be accommodated elsewhere.

In my opinion, if anything, such proposals should be treated at least as strictly as a proposed rezoning of a community, or trigger a rezoning of the community to account for future development potential. Currently, landmarking is categorically excluded from such reviews.

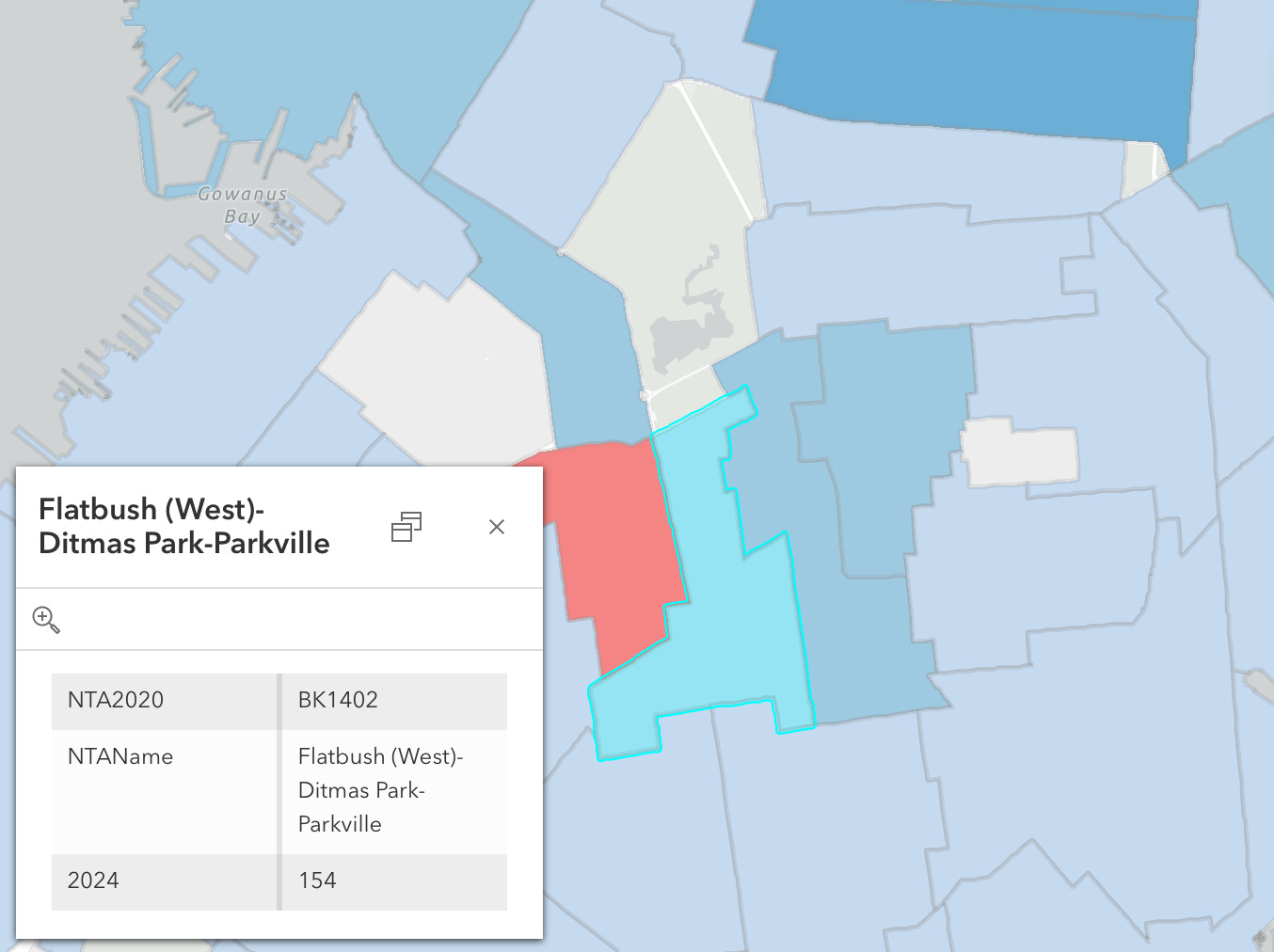

The Racial Equity Report analysis in this case similarly avoids a thorny issue. It reports percentage increases in housing production in the larger area without acknowledging that the absolute numbers are extremely low – just 154 units in 2024 in the immediate area. Community Board 14 remains among the lowest producers of affordable housing in the city, despite strong transit access and proximity to jobs. You would not be able to easily tell that from the information presented.

The result is a process in which permanent land-use restrictions are approved with little public consideration of their costs.

Who Benefits From Landmarking?

As a city planner once told me, New York is simultaneously over-landmarked in wealthy neighborhoods and under-landmarked everywhere else. For example, there is no Bronx Art Deco historic district. Nor has LPC designated nonprofit and publicly-assisted housing developments that are genuinely historically important.

Research from NYU’s Furman Center shows that residents of historic districts in New York City are disproportionately white, affluent, and highly educated compared to residents of non-landmarked areas. Property values in historic districts tend to be higher, and appreciation rates are often stronger after designation, particularly in already desirable neighborhoods.

The proposed districts in Victorian Flatbush fit this pattern. Homes in Beverley Square West have been selling for over a million dollars for almost two decades, recently for as much as $2–3 million, implying monthly housing costs well above the median income of Community Board 14 as a whole.

Large-scale landmarking is also not demand-neutral. It requires sustained political organizing and familiarity with administrative processes, as well as willingness to bear the cost, which also give an advantage to well-resourced homeowners. The city is not about to assume responsibility for preserving structures that have no income to maintain them.

The result is a system in which political influence can be converted into permanent land-use control. By freezing existing conditions, landmarking also protects the preferences of a narrow group, while shifting the costs of housing scarcity—higher rents, longer commutes, overcrowding—onto everyone else.

When large transit-rich, low-density areas are removed from the city’s future housing capacity, growth pressure doesn’t disappear—it is displaced to fewer neighborhoods, often those with less political power and fewer preservation protections.

This is not an argument against historic preservation. It is an argument against treating preservation separately from its distributional consequences and from the housing market.

What the Council and the Mayor Should Do

The City Council’s and Mayor Mamdani’s decisions are not about whether Victorian architecture is worthy of preservation; that has already been decided by the LPC. They are about tradeoffs.

Preservation has value. But so does housing near subway lines. If the city wants to be affordable, it cannot keep converting transit-rich neighborhoods into permanently downzoned enclaves that expand as the areas gentrify.

The Mamdani administration should review the existing historic districts for consistency with their housing plans and be cautious about designating new ones, keeping in mind that LPC designation functions as super-restrictive zoning in affluent neighborhoods as a practical matter.

New York isn’t a museum. And a forward-looking city should be building new neighborhoods worthy to be considered for preservation a hundred years from now.

Full disclosure: I live in one of the newly designated districts.

Why can't NYC do this and provide housing as well? Look at European cities, they have preserved their architecture in many places. Amsterdam is a prime example. If they Dutch can do this we can too. WHy must everything be bulldozed under every generation in the US?

And don’t assume that every resident in the LPC or proposed one is in favor. I own in a relatively recent district and it seemed that a group of outsiders were the ones to initiate and advocate on its behalf. Owners like me weren’t happy to have yet another city agency to contend with. If the municipality government can’t pick up the trash reliably, why should they opine on the paint color of my building?