Under Mamdani, a Welfare Revival Looms

A city can be known as a place where government, to a maximum degree, takes care of everything everybody needs, or as a beacon of opportunity. There’s no precedent for both.

New York’s bad old days were characterized by high crime and high rates of welfare usage. That second problem developed in response to a stagnating local economy coupled with a local culture of leniency towards expansive benefit recipients. Those same conditions now prevail. Therefore, under Zohran Mamdani, and just in time for next year’s 30th anniversary of welfare reform, New York looks well-poised for a welfare revival.

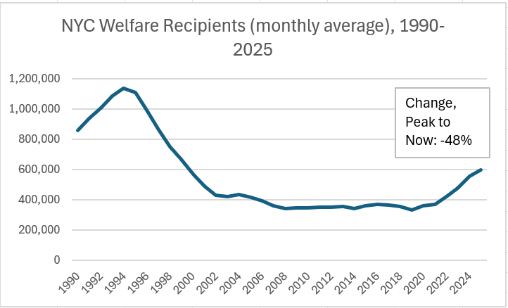

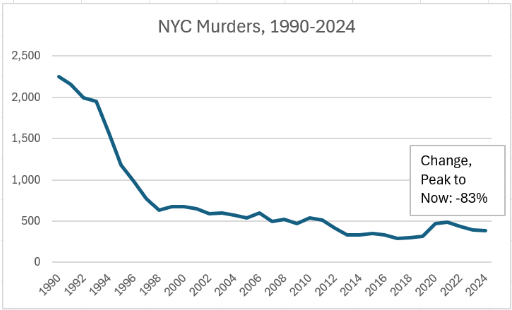

As the above graphs show, murders are still way down from the bad old days’ peak but, of late, welfare has risen markedly. And yet, in public debate, crime concerns remain salient, but New Yorkers care far less about dependency than they did 30, or even ten years ago. I can personally attest that it was much easier to raise concerns about the modest growth in welfare enrollment Bill de Blasio oversaw than the recent and more dramatic enrollment increase under Eric Adams. The issue did not register at all during the 2025 mayoral campaign.

For four reasons, New Yorkers should be more concerned about rising dependency than they are.

First, the budgetary impact. Last fiscal year’s bill for public assistance grants was $2.6 billion, with city taxpayers footing half the cost. In FY20, before the recent surge, city taxpayers spent $500 million less on public assistance grants.

Second, New York’s abandonment of welfare reform constitutes a highly non-evidence-based policy move.

Welfare reform, which New York City began implementing before federal law required it: had two main thrusts: (1) making access to cash benefits contingent on work or pursuing work (“workfare”) (2) prioritizing rapid job placement over education and training (“work first”). This agenda succeeded: not only did the number of New Yorkers on welfare plunge (see graph above), but between the mid-1990s and late 2000s, work rates for single mothers in New York rose from 43 to 63 percent and the child poverty rate fell from 42 to 28 percent. Welfare reform policies met with success elsewhere, too. In his recent book Reforming Social Services in New York City, political scientist Thomas Main notes that welfare reform long enjoyed a consensus reputation as one of the most “evidence-based” things American government did.

The Great Society regime, which lasted from the 1960s until the 1990s, had offered one solution to poverty, centered around investment in education and training to get low income minorities into “good” jobs, and the prioritization of benefit access over promoting work. Welfare reform reordered those priorities. Giuliani and Bloomberg argued that promoting work was as essential to a welfare office’s function as easing benefit access and that education and training should build on, not replace, work experience.

Bloomberg successor, Bill de Blasio, reversed course on both the workfare and work first fronts, restoring the old Great Society consensus. The Adams administration demonstrated its conformity to that consensus with the glacial pace at which it re-instituted work requirements after they were temporarily suspended during COVID. Under Adams, Human Resources Administration job placements fell off a cliff, from over 40,000 during late de Blasio to less than 10,000 under Adams (they’ve recently picked up but remain still well below historic norms). Since January 2022, when Adams took office, welfare recipients are up over 50% in New York City but only up 15% in the rest of New York State. Last year, EJ McMahon noted the symbolic significance of Eric Adams’ renaming “Job Centers” as “Benefit Access Centers”, a title very close to what they were known as before welfare reform: “Income Maintenance Centers.”

We can expect more of the same under Mamdani: getting people out poverty has more to do with signing them up for benefits than getting them working, and best to pursue education and training until a “good” job materializes, if it ever does.

Third, independent of any ideologically-motivated push Mamdanians might make to expand benefit usage, welfare enrollment looks set to grow, or at least stabilize at the current elevated levels thanks to a mediocre economy. In their most recent analyses of the New York economy, both the city and state comptrollers express pessimism about the local labor market’s prospects (“lackluster” “employment growth is projected to slow significantly”).

Under past administrations, even recessions failed to slow welfare reform’s progress (see graph above). But that entailed a degree of commitment in the city social services bureaucracy that no longer exists.

The fourth reason to care about rising welfare dependency in New York is that it will motivate more working and middle class outmigration.

Progressive scholars disparage welfare reform as a neoliberal conspiracy. And yet, polls continue to show strong public support for the principle that, for able-bodied adults, benefits should be contingent on work. Every neighborhood is composed of idle and active elements. When the balance tips too much towards the former, social dysfunction, followed by population loss, will result. Working class parents don’t want to raise kids in an environment surrounded by an abundance of adults who could be working but aren’t. Neighborhoods vary greatly their rates of benefit usage.

Welfare reform was never about slashing the safety net, for, even as cash assistance enrollment went down, Medicaid and Food Stamps expanded. Bloomberg officials especially cast that as a feature, not a bug, with respect to their agenda on upward mobility. Non-cash benefits were “work supports” that helped “make work pay”. “If you work, we will help you” was Bloomberg HRA chief Robert Doar’s refrain. Managed poorly, though, a government benefit package can transition from supporting work to replacing it.

When over one million New Yorkers drew welfare, economic officials despaired over a growth model that had once provided unprecedented opportunity to generations of immigrants and other strivers but had subsequently broken down. New York yet has some ways to go before welfare enrollment re-attains its former peak. But progressive officials should tread carefully with their ideas about expansive reliance on government benefits as a sign of social health. Reputationally, a city can be known as a place where government, to a maximum degree, takes care of everything everybody needs, or as a beacon of opportunity. There’s no precedent for both. A choice will have to be made.

Stephen Eide is a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute and a contributing editor of City Journal.

What are you talking about? The municipal budget has grown twice as fast as CPI and population combined since the last fiscal crisis, which was brought about entirely by Lindsay's runaway spending.

We have free pre-K. We have EBT and very low prices in the boroughs where people who earn low incomes live (they're not "low income people" - they're people who earn low incomes - income is what you do, not what you are). We have half-price bus and subway fare. We have NYCHA.

We have done it your way for 50 years, benefiting from the windfall that is the fact that when the Fed prints new money to fulfill its Keynesian fantasies, the money flows through NYC.

We also already have the most top-heavy tax system in the world. The top 5% of NYC taxpayers pay almost all the taxes. And people walking around paying a few hundred dollars a year complain, "tax the rich." We already do.

Doubling down on what has failed for 50 years is insanity.